struggling to hold the movement together. This placed them in opposition to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League, which criticized the slogan in no uncertain terms, leaving Dr. Humphrey castigated it as reverse racism, declaring that “there is no room in America for racism of any color.” 3 Within the civil rights coalition Black Power precipitated a decisive split, as both the SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) embraced versions of Black Power, dropped their commitment to nonviolence, and questioned the value of interracialism. For its critics, Black Power symbolized a dangerous new force and conjured up images of “Black Jacobinism” and the “Mau Mau . . . coming to the suburbs at night.” 2 Vice President Hubert H. The sudden emergence of the “Black Power” slogan created a political firestorm within both the civil rights movement and the broader body politic. What do you want?” The crowd thundered back, “Black Power!” 1

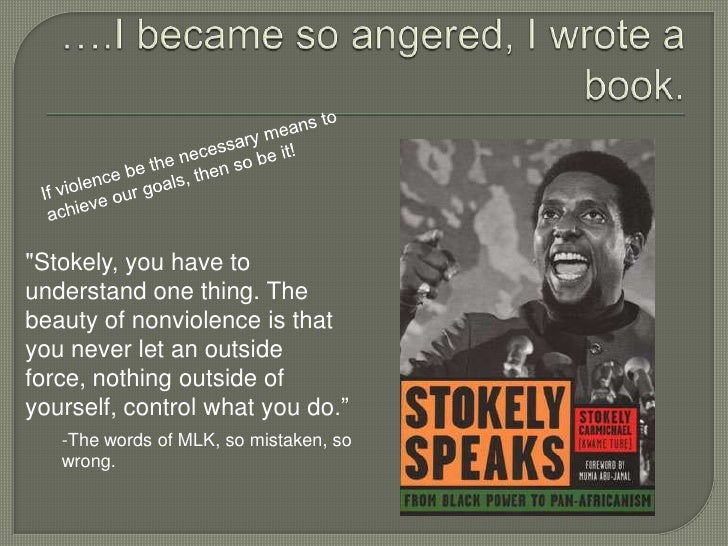

What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!” Carmichael proclaimed that “every courthouse in Mississippi ought to be burned tomorrow to get rid of the dirt . . . from now on when they ask what you want, you know what to tell 'em.

We been saying freedom for six years and we ain't got nothin'. “The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin' us is to take over. “This is the 27 th time I have been arrested-and I ain't going to jail no more, I ain't going to jail no more,” he told the several hundred mostly local African Americans. The SNCC leader had been released from jail minutes before and acknowledged the “roar” of the angry crowd with a “raised arm and a clenched fist” as he moved forward to speak. O n the evening of 17 June 1966, Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), addressed a rally in Greenwood, Mississippi. John Morsell, NAACP assistant executive director, 3 November 1966 I ntroduction

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)